Photo source: EquiManagement

Written by: Arabella Kats, Staff Writer

MOVEMENT: Previously unseen, donkeys are now a part of many Riversiders’ daily lives as they migrate into suburban areas.

Riverside residents have started noticing an increase in wildlife activity in the neighborhoods near the Box Spring Mountains, namely in the form of the wild donkeys (or burros) that have inhabited the northeastern hills of Riverside for decades. However, their increasingly frequent appearances concern some, posing questions relating to how their presence may affect locals in those areas. The perspectives of two experts and a longtime Riverside resident reveal information which can help people better understand the burros and how to act when around them.

Fifteen years ago, it would have been very difficult to spot a wild donkey without traversing deep into the hills and wild areas of the Inland Empire. However, this has changed in the last decade. One Riverside resident of over thirty years, Vanda Yamaguchi, mentioned that “five years ago I only saw them occasionally, but now I see them almost every day.” Several other people have reported sightings of wild burros in the area in between the University of California Riverside (UCR) and the Box Spring Mountains. Dr. Kenneth Halama, a director in the Natural Reserve System (NRS) at UCR recalled that “if I drive up to the… Box Spring Reserve, I see them… along Pigeon Pass Road.” The most likely cause for this migration, as explained by both Dr. Halama and Associate Professor Preston Galusky from the Anatomy and Physiology department at Riverside City College (RCC), is the lack of water and food due to the “ongoing drought that we’re experiencing right now… [that] kicked off in 2000-2001.” New housing developments are also encroaching on the donkey’s habitat and forcing them to move elsewhere, which often happens to be in already-existing neighborhoods.

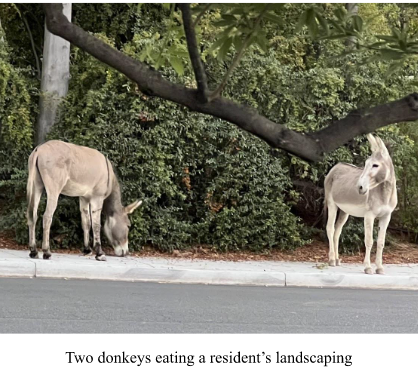

Because the donkeys have adapted to feed on mostly desert shrubs and herbaceous vegetation, Professor Galusky expects “they can tolerate an awful lot,” and noticed that they seem to enjoy eating grass from people’s front lawns. “That’s probably a treat for them, I imagine,” he chuckled; unfortunately, this means that burros will likely eat and damage other residential landscaping as well. In addition, what goes in one end must come out the other, and the burros hold no reservations regarding where they evacuate. It is not uncommon to find their feces littering the sidewalks and streets they frequent. Alongside the destruction of greenery, these droppings propose the question of whether or not the donkeys can properly adapt to living in suburban areas. It “depends on how tolerant people are of having them around… [and] whether people want them around” Dr. Halama said; however, “if they become too numerous, something is going to need to be done.”

One mystery surrounding the donkeys regards their origins and their history in the Inland Empire area. Both Professor Galusky and Dr. Halama agreed that the donkeys have been around a long time, though neither are exactly sure how they arrived. Professor Galusky, citing a theory, proposed that the donkeys first arrived between the late 1800’s and the early 1900’s, during the California gold rush, when prospectors came to California in search of gold, bringing donkeys yet abandoning them when their prospecting proved to be less than fruitful. Though this theory may not be proven, Dr. Halama emphasized that “the donkeys… were at one point… domestic, but now they’re feral.”

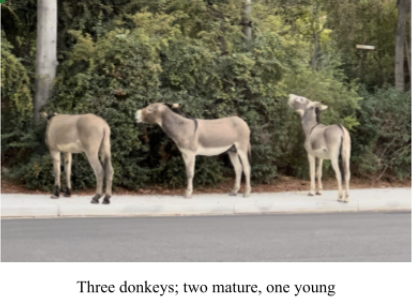

While the burros tend to be very gentle and are generally passive, Professor Galusky warns that they are very big animals, and a collision with a car could be dangerous for both the driver and the donkey. According to Galusky, while a fully mature herd is not likely to be aggressive, they may act defensively if threatened, “especially if there are younger donkeys around.” Dr. Halama reinforced this idea : the donkeys are protective of their young and “any… animal like that is unpredictable,” Halama claimed, “you don’t know what it’s going to do… so personally, I would steer clear.” Mrs. Yamaguchi added that a donkey recently kicked a dog belonging to a friend of hers, suggesting that “it is probably better to keep pets and children away from the animals.” Oftentimes, she even sees students near UCR feeding and taking selfies with the burros, some even in their cars and thereby conditioning the donkeys to approach cars instead of avoiding them, which can result in serious accidents.

Riverside’s donkeys are fascinating creatures dating back to the days of the California Gold Rush, and they now range from Riverside, to Moreno Valley, to the San Timoteo Badlands. While it is generally harmless, human-donkey interaction is less than advisable, as the donkey’s are wild animals and may act unpredictable under stress. Unfortunately, they can also be destructive forces within suburban areas and may eventually need to be relocated, but for now we can enjoy seeing them around from time to time.

For additional information regarding the rescue, rehabilitation, and protection of the donkeys, visit donkeyland.org