BLOCKBUSTERS: Movies are no longer what they used to be.

By Cole Nelson, Diversions Editor

If you were to go to the beach during the summer of 1975, you would be considered a brave (and possibly idiotic) soul for simply stepping foot in the water. People all around the world avoided the ocean, afraid of what lay underneath the foamy waters. This was the result of Steven Spielberg’s classic horror film Jaws. Jaws made a profound impact then, and continues to influence American culture today. Although it is considered a classic film—Jaws demonstrates great technical skill from a young Spielberg—it introduced a craze that swept the nation for years to come; it established the beginning of summer blockbusters.

Fast-forward nearly forty years to today. Films have changed immensely: the quality of production has improved, movies’ budgets soared, audiences have grown and digitized visual effects have become the norm. But above all, one thing has remained the same; the summer blockbuster continues to be the most diversely admired form of entertainment.

Each year, production companies pilot yet another (or even several) action-packed film to the big screen, where it produces a profit that is exponentially larger than its already hefty budget. But why not? Currently, it is what attracts the largest amount of moviegoers; everyone loves a well-exaggerated explosion.

The reasoning for this change in movie tastes (from classic to contemporary) stems from two separate things. The first originates from the Baby Boom era. During the 1950’s, film studios began incorporating new and improved inventions—a 3D viewing experience and a widescreen format being two of the more popular ones—to compete with the free and easily accessible television productions. Throughout this time, the demographic of moviegoers changed from housewives to teenage boys, which created an audience interest that was less pro-war (World War II had ended by this time) and leaned more towards rebellious and (consequently) violent subject matter. By 1968, the former Hays Code of film restriction was replaced by the current MPAA rating system, which allows more controversial topics to be shown to a much younger audience. As a result, the film audience is occupied by a teenage majority who prefers visually pleasing content (explosions and saturated colors) to structural content. Nevertheless, film is a visual medium.

The second reasoning has to do with the vast increase in digital technology. The word film no longer represents the method of movie making; it has become obsolete due to digitization. New technology affixes ease and convenience in filmmaking, much like what the television did to entertainment. Complete film sets can now be built on a computer by a supremely talented special effects team. One can tap into an ocean of unseen imagination and share it for the world to see. Of course, it is human nature to be interested in concepts of supernatural power and the intangible. The ease of digitization offers filmmakers the ability to portray these interests to an international audience. This may indicate an explanation as to why large, transforming robots from outer space generate such a large amount of revenue. It is the content of the visuals, again, that amuses the audiences rather than the quality of the story. Digital technology supplies these desirable visuals and movie makers exploit this technology.

It is a constant fear of mine that the film industry is straying too far away from its former century self into the age of digitization where structural content no longer holds popularity. The majority of popular contemporary movies are either overflowing with intense fight sequences or are glorified remakes of considerably timeless films. While some believe that the Great Hollywood Era is among us once more with films such as Gravity, 12 Years a Slave and Captain Phillips, I disagree. The age of passivity in the audience will always be present as long as movies are produced to provide pleasure without contemplation. However, as reassurance, I recall the initial infamous reaction to such illustrious classics such as Casablanca, Citizen Kane and The Shining. It took several years—and an overwhelming amount of LSD-tripped hippies—for 2001: A Space Odyssey to receive any sort of reputation. As Francois Rabelais says, “It is my feeling that Time ripens all things.” There may be hope after all.

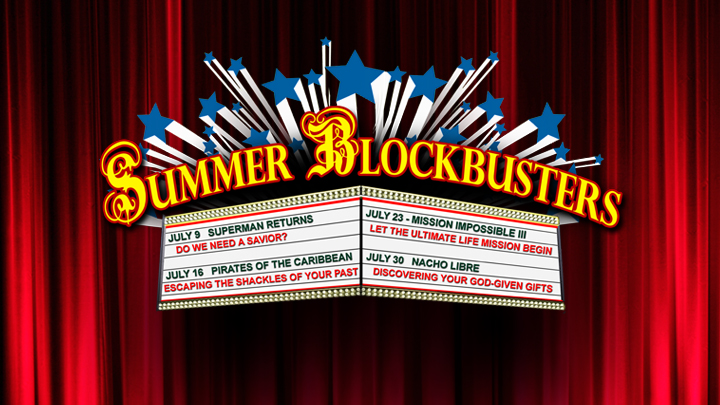

Photo courtesy of www.keystonechurch.com